The humerus is the largest bone in the upper limb, extending from the shoulder to the elbow, playing a crucial role in arm movement and stability․

1․1 Overview of the Humerus Bone

The humerus is a long bone located in the upper arm, extending from the shoulder to the elbow․ It is the longest and largest bone in the upper limb, serving as the primary structural component of the arm․ The humerus connects the scapula at the shoulder joint and the radius and ulna bones at the elbow joint․ Its unique anatomy includes a rounded head at the proximal end, which articulates with the glenoid cavity of the scapula, and condyles at the distal end for elbow joint articulation․ The bone also features prominent tubercles and grooves that facilitate muscle and nerve attachments, enabling a wide range of arm movements․ This bone is essential for both mobility and stability in the upper limb․

1․2 Key Terminology in Humerus Anatomy

Understanding key terms is essential for studying the humerus․ The proximal end refers to the portion near the shoulder, while the distal end is closer to the elbow․ The shaft is the long, cylindrical part connecting these ends․ Epicondyles are bony projections at the elbow, providing muscle attachments․ Tubercles (greater and lesser) are prominences near the head for muscle insertion․ The anatomical neck is a groove below the head, and the surgical neck is a narrower region just below․ The deltoid tuberosity is a roughened area for muscle attachment, while the radial groove houses the radial nerve․ These terms form the foundation for understanding humerus anatomy․

Proximal End of the Humerus

The proximal end of the humerus includes the head, anatomical neck, greater and lesser tubercles, and surgical neck․ These structures facilitate shoulder movement and muscle attachment, vital for arm function and stability․

2․1 The Head of the Humerus

The head of the humerus is a rounded, smooth structure located at the proximal end of the bone․ It articulates with the glenoid cavity of the scapula, forming the glenohumeral joint․ This joint allows for a wide range of shoulder movements, including flexion, extension, abduction, and rotation․ The head is covered with articular cartilage, which reduces friction during these movements․ It is connected to the rest of the humerus through the anatomical neck, a slight narrowing just below the head․ The head of the humerus is a critical component for upper limb mobility and stability, enabling activities such as throwing, lifting, and reaching․

2․2 Anatomical Neck

The anatomical neck of the humerus is a narrow region located just below the head of the bone․ It is a smooth, slightly constricted area that serves as the transition zone between the head and the greater and lesser tubercles․ The anatomical neck is an important landmark for surgical procedures and anatomical studies․ It is also a site where muscles and ligaments attach, providing stability to the shoulder joint․ The axillary nerve and posterior circumflex humeral artery pass near this region, making it clinically significant․ Injuries or fractures in this area can affect shoulder mobility and function, requiring careful medical attention․

2․3 Greater and Lesser Tubercles

The greater and lesser tubercles are prominent bony projections on the proximal humerus, located laterally and medially, respectively; The greater tubercle is the larger of the two and serves as an attachment point for muscles such as the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor․ The lesser tubercle, smaller and more medially positioned, is where the subscapularis muscle attaches․ These tubercles are vital for shoulder movement and stability, facilitating actions like abduction, rotation, and adduction․ Fractures or injuries to these areas can impair shoulder function, making them clinically significant in orthopedic assessments and treatments․

2․4 Surgical Neck

The surgical neck of the humerus is located just distal to the greater and lesser tubercles․ It is a common site for fractures due to its anatomical position and vulnerability during falls or trauma․ This area is significant in clinical settings as it lies near the radial nerve and axillary artery, making surgical interventions complex․ The surgical neck is also a frequent target in orthopedic procedures, such as fracture reductions or shoulder surgeries, due to its proximity to the shoulder joint and surrounding musculature․ Understanding its anatomy is crucial for effective treatment and minimizing complications in humeral injuries․

Shaft of the Humerus

The shaft of the humerus, or diaphysis, is a long, cylindrical structure connecting the proximal and distal ends․ It provides extensive muscle attachments for arm movement and stability․

3․1 Structure of the Humerus Shaft

The humerus shaft, or diaphysis, is a long, cylindrical structure connecting the proximal and distal ends․ It is composed of compact bone, with a medullary cavity containing bone marrow․ The shaft is narrower distally and features a roughened surface for muscle attachments; Anteriorly, it is smooth, while the posterior surface is marked by the spiral groove, housing the radial nerve and deep brachial artery․ This structure provides a robust framework for muscle insertion, enabling forearm and shoulder movements․ The shaft’s design balances strength and flexibility, essential for upper limb function and mobility․ Its anatomical features are critical for both stability and dynamic movement․

3․2 Deltoid Tuberosity

The deltoid tuberosity is a prominent, roughened area located on the lateral aspect of the humerus shaft, approximately midway between the shoulder and elbow․ It serves as the insertion point for the deltoid muscle, which is responsible for shoulder flexion, extension, and rotation․ This tuberosity is a key anatomical landmark, providing a secure attachment site for the muscle’s tendinous fibers․ Its location along the shaft allows for efficient transmission of forces during arm movements․ The deltoid tuberosity is also clinically significant, as injuries or fractures in this region can impact shoulder mobility and overall upper limb function․ Its structure and position are vital for normal arm mechanics․

3․3 Radial Groove (Spiral Groove)

The radial groove, also known as the spiral groove, is a notable anatomical feature on the posterior surface of the humerus shaft․ It begins near the surgical neck and spirals distally along the bone․ This groove provides a protected pathway for the radial nerve and the deep brachial artery as they descend from the shoulder toward the forearm․ The radial groove is narrow and deep, ensuring that these vital structures are shielded during muscle contractions; Its spiral nature allows for flexibility and protection as the arm moves․ This groove is a critical anatomical landmark, particularly for surgeons and anatomists, due to its role in housing important neurovascular structures and its involvement in various clinical procedures․

Distal End of the Humerus

The distal end of the humerus forms the elbow joint, connecting to the radius and ulna bones of the forearm․ It features condyles for articulation and epicondyles for muscle attachment, providing stability and movement to the elbow joint․

4․1 Condyles of the Humerus

The condyles of the humerus are located at the distal end and are crucial for elbow joint articulation․ The medial condyle, larger and weight-bearing, articulates with the ulna, while the lateral condyle articulates with the radius․ Together, they form a hinge joint, enabling flexion and extension․ The condyles are separated by a groove for nerve and blood vessel passage․ Their smooth surfaces ensure efficient movement․ The medial epicondyle and lateral epicondyle are adjacent, serving as muscle attachments․ The supracondylar ridge strengthens the distal humerus, while the medial and lateral supracondylar ridges provide additional structural support․ These features ensure stability and mobility at the elbow joint, with the median and radial nerves nearby․ Proper alignment of the condyles is vital for normal elbow function and overall upper limb mobility․

4․2 Epicondyles (Medial and Lateral)

The medial and lateral epicondyles are bony prominences located on the distal humerus, serving as attachment points for muscles and ligaments․ The medial epicondyle is larger and provides attachment for the ulnar nerve, while the lateral epicondyle is smaller and associated with the radial nerve․ Both epicondyles are crucial for forearm and finger movements․ The medial epicondyle is the origin of flexor muscles, and the lateral epicondyle is the origin of extensor muscles․ These structures are essential for upper limb mobility and function․ The epicondyles also provide structural support to the elbow joint and protect nearby nerves, ensuring proper innervation and movement of the forearm and hand․

4․3 Supracondylar Ridge

The supracondylar ridge is a prominent bony ridge located above the condyles on the distal humerus․ It serves as an anatomical landmark and attachment site for muscles․ The ridge is divided into medial and lateral parts, with the medial supracondylar ridge being more pronounced․ It provides insertion points for forearm flexor muscles, while the lateral ridge supports extensor muscles․ The ridge also lies close to the median and radial nerves, which run nearby․ Fractures in this area are common and can affect nerve function․ The supracondylar ridge plays a critical role in elbow movement and stability, making it a key structure in humerus anatomy․

Muscles and Nerves Associated with the Humerus

The humerus connects to 13 muscles, enabling arm movement․ Key nerves like the radial and median nerves run nearby, facilitating sensory and motor functions․

5․1 Major Muscles Attached to the Humerus

The humerus serves as an attachment point for several major muscles, including the pectoralis major, teres major, latissimus dorsi, deltoid, and triceps brachii․ These muscles facilitate various movements such as flexion, extension, and rotation of the arm․ The pectoralis major originates from the chest and assists in adduction and flexion․ The latissimus dorsi, one of the largest back muscles, helps in extension and adduction․ The deltoid muscle, covering the shoulder, enables flexion, extension, and rotation․ The triceps brachii, located posteriorly, is responsible for elbow extension․ These muscles collectively provide a wide range of motion to the upper limb, making the humerus a critical structure for functional mobility․

5․2 Nerve Supply and Innervation

The humerus receives its nerve supply from branches of the brachial plexus, which innervates the upper limb․ The radial nerve runs through the spiral groove of the humerus, providing sensation to the back of the arm and hand․ The median nerve, originating from the brachial plexus, passes near the distal humerus and supplies the anterior forearm muscles and sensation to the palm․ The ulnar nerve, also branching from the brachial plexus, travels posteriorly near the medial epicondyle, supplying the flexor muscles of the forearm and sensation to the little finger․ These nerves are crucial for motor and sensory functions of the arm and hand․

Clinical Relevance of Humerus Anatomy

Understanding humerus anatomy is crucial for diagnosing fractures, nerve injuries, and planning surgeries․ Fractures near the proximal or distal ends often require precise treatment to restore function and mobility․

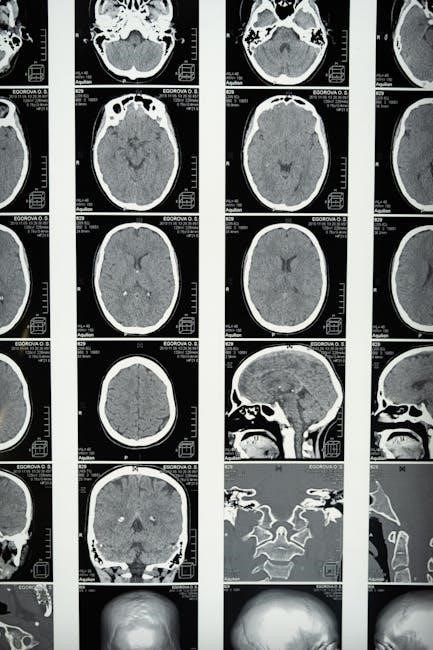

6․1 Common Fractures of the Humerus

The humerus is prone to various fractures, with the proximal end being the most common site․ Proximal humerus fractures often occur in older adults due to osteoporosis or falls․ These fractures can involve the head, neck, or tuberosities and may require surgical intervention․ Another prevalent type is the supracondylar fracture, typically seen in children, which occurs just above the elbow; Midshaft fractures often result from high-energy trauma, such as car accidents or sports injuries․ Distal humerus fractures, near the elbow, can affect the condyles and may complicate forearm movement․ Understanding these fracture patterns is essential for accurate diagnosis and effective treatment planning․

6․2 Surgical and Therapeutic Implications

Surgical interventions for humerus-related injuries often involve open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) to restore alignment and stability․ In severe cases, such as complex fractures or joint damage, hemiarthroplasty or total shoulder arthroplasty may be necessary․ Physical therapy plays a crucial role in post-surgical recovery, focusing on regaining strength and mobility․ Non-surgical treatments include immobilization with casts or braces, along with pain management strategies․ Nerve damage, particularly involving the radial or ulnar nerves, may require specialized rehabilitation․ Understanding the anatomical landmarks, such as the radial groove, is critical for precise surgical planning and minimizing complications․

The humerus, as the largest bone in the upper limb, is vital for arm movement and stability, connecting the shoulder and elbow while supporting complex anatomical functions․

7․1 Key Points About the Humerus

The humerus is the longest and largest bone in the upper limb, connecting the shoulder and elbow․ It features a proximal head articulating with the glenoid cavity, an anatomical neck, and tubercles for muscle attachment․ The shaft includes the deltoid tuberosity and radial groove for nerve passage․ Distally, it forms condyles and epicondyles for forearm muscle attachments․ The humerus is crucial for arm movement and stability, with 13 muscles attached․ Its anatomy is vital for understanding injuries, fractures, and surgical interventions․ Proper knowledge of the humerus aids in diagnosis and treatment of upper limb conditions, emphasizing its importance in both clinical and anatomical studies․